Marginal Wells 101: What are they, where are they, and why do we need to assess them?

Low-producing oil and gas wells need targeted measurement, greater transparency, and stricter oversight.

Over half a million oil and gas wells in the United States produced 15 barrels of oil equivalent (BOE) or less daily in 2023 (according to RMI analysis using Enverus and Rextag). These low-producing wells, called marginal wells, comprise three-quarters of all US oil- and gas-producing wells. At most, these wells extract less than 630 gallons a day — enough to fill just eight bathtubs. But most of these wells produce far less than that. Almost half of marginal wells are submarginal wells or “micro producers” that produce one BOE or less per day — not enough to fill one bathtub.

Marginal wells are often overlooked. While government records generally have their location, volume, owner, and operator, marginal wells are often hidden in plain sight, receiving little attention from communities and regulators. These wells, like all oil and gas systems, are a significant source of methane, which causes fires and explosions, contributes to smog, and heats the planet over 80 times more powerfully than carbon dioxide.

Marginal wells also emit dangerous air toxins and volatile organic compounds (including benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylene, and hydrogen sulfide) that can sicken people by polluting air, water, and land. The effects on surrounding communities can amount to far greater impacts than the marginal economic benefits gained. And nearly one in ten Americans live in a county with over 1,000 marginal wells.

The small production volumes of marginal wells can make their operations highly emissions intensive and wasteful. Given their massive numbers and heightened risk of being abandoned, targeted measurement, greater transparency, and stricter oversight are merited.

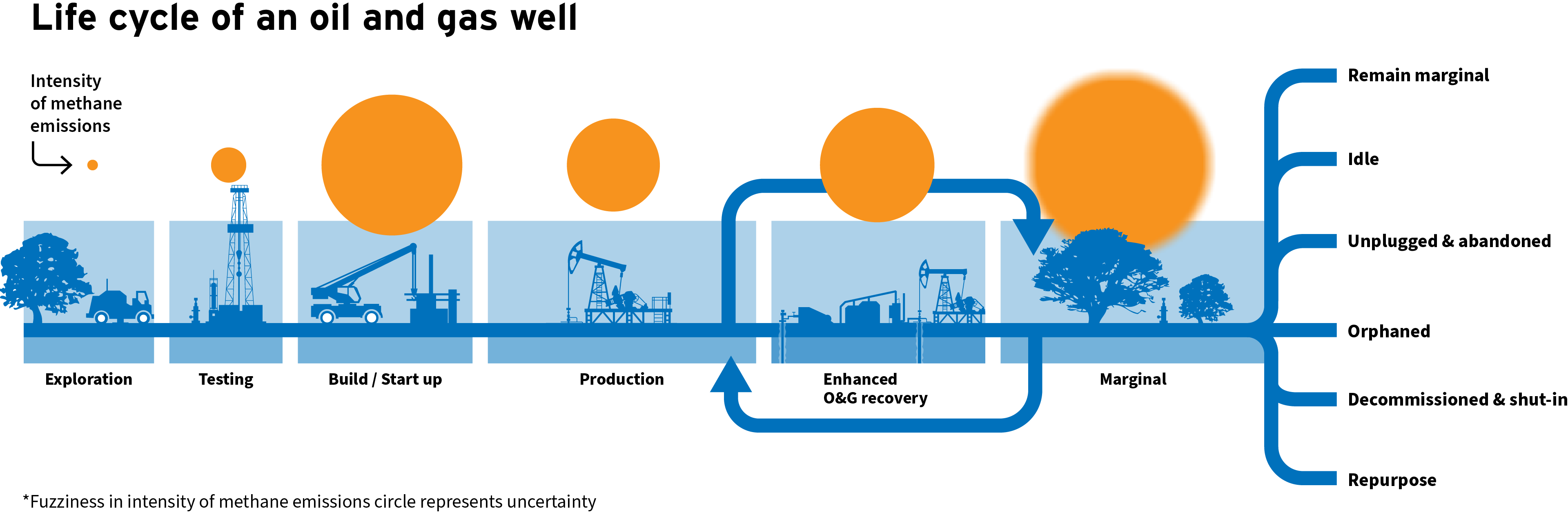

Charting the life cycle of a well

The life cycle of an oil and gas well often extends beyond its production heyday. After a well is drilled, gas tends to be flared and vented until system pressures and volumes stabilize. Once the system settles, a well enters its decades-long production phase working toward its peak. After reaching its peak, the well’s production begins to decline, spurring operators to boost production, for example by injecting water or gas, fracturing wells, or using other enhanced recovery methods. Eventually these interventions to get more usable product from the well provide diminishing returns and the well’s production level drops until it is categorized as “marginal.”

At this point, larger oil and gas companies often sell these low-producing wells to smaller operators with lower profit thresholds. Largely hidden in plain sight, most marginal wells continue to produce for generations, as shown by the number of marginal wells more than 20 years old in Exhibit 1. While some are properly decommissioned, plugged, and permanently shut in, many low-producing wells run the risk of being idled, abandoned, or orphaned, ultimately creating unrecoverable costs and damages to communities, governments, and companies.

Exhibit 1: US active oil- and gas-producing wells by age in 2023

Notes: Well age calculated from a well’s spud date. Spud date data was not available for 10 percent of US active oil and gas wells. Submarginal wells are a subcategory of marginal wells.

RMI Graphic. Source: RMI Analysis using Enverus data

The growing population of marginal wells

From permitting to collecting royalties, states track and keep records on oil and gas wells. Based on 2023 data from Enverus, states reported 575,000 US wells producing, on average, less than or equal to 15 BOE of oil and gas per day. The population of these marginal wells has increased almost 20 percent since 2000, and submarginal well counts are up over 30 percent (as shown in Exhibit 2). Although marginal wells account for the vast majority (75 percent) of all producing US oil and gas wells, in aggregate they represent minimal production volume — only 5 percent of the reported 12.1 billion BOE of total US oil and gas supplies in 2023.

Exhibit 2: Total US active oil- and gas-producing wells by production rate brackets

Notes: Marginal wells produce > 0 and ≤ 15 BOE/day (blue area). Submarginal wells produce > 0 and ≤ 1 BOE/day (dark blue area). RMI Graphic. Source: RMI Analysis using Enverus data

From these trends, two things are clear. First, the United States has a massive number of marginal wells to contend with, especially if they were to become abandoned and orphaned with no responsible party to attend to them. And second, the growing sizeable share of submarginal “micro-producing” wells is alarming because the smaller a well’s production, the more likely its leakage leads to highly emissions-intensive operations.

Living near marginal wells

Major volumes of oil and gas production are associated with a few select states. Together, Texas, New Mexico, and Pennsylvania produce over one-half of US oil and gas. But when it comes to the over half a million marginal wells in the United States, numerous states lay claim to them, as shown in Exhibit 3.

Exhibit 3: Population of US marginal wells, by state (2023)

RMI Graphic. Source: RMI Analysis using Enverus data. Note: See RMI’s new Marginal Well Tracker tool

Based on 2023 population data, nearly one in ten Americans live in a county with over 1,000 marginal wells. In California, West Virginia, and Wyoming, for example, approximately three in ten people live in a county with over 1,000 marginal wells. The states with the highest percentage of their wells categorized as marginal include New York, Virginia, Nebraska, Kansas, West Virginia, and Ohio. And most have not actively produced significant amounts of oil or gas in generations.

The need for emissions data

Oil and gas is an inherently leaky business. It doesn’t take a large leak for marginal wells to waste a meaningful share of its small production. Conversely, nonmarginal wells leak somewhat but produce a lot — unless they are found to be super emitters. Consequently, marginal wells typically have very high emissions intensities (emissions per BOE produced) compared to nonmarginal wells.

While some states like Colorado are actively measuring their marginal wells’ gas loss and emissions, this critical data is largely missing across the United States. One study found that a lack of comprehensive maintenance on old and outdated equipment may be the main emissions driver. Still, too little is known about marginal wells especially compared to nonmarginal wells, which tend to be better maintained, more frequently monitored, and subject to tighter regulation.

Although emissions for a marginal well may be relatively small compared to nonmarginal wells, aggregated over hundreds of thousands of marginal wells, the waste adds up. For example, one government study estimated that marginal wells accounted for 60 percent of methane emissions from US natural gas production and 40 percent from US oil production in 2021. An EDF study found that low-production well sites contribute roughly half of all oil and gas well site methane emissions.

Updated and differentiated marginal well emissions data is needed to prioritize mitigation opportunities. Their sheer number means that it will be difficult if not impossible to attend to every US marginal well.

Next steps for action

US policymakers have incentivized marginal wells for over a century with tax credits that spur their continued operation. Yet, their insignificant contribution to US production — especially compared to America’s surging oil and gas volumes — makes it unclear why US policies continue to promote marginal wells.

This political blind spot is amplified by a data gap when it comes to marginal wells. While it is widely recognized that marginal well emissions are an unsolved problem, their environment, health, and safety impacts are not well characterized. Further studies that take measurements to differentiate the most wasteful and polluting marginal wells can help prioritize their proper shut in and avoid their abandonment.

Like Colorado, other states should conduct ground-based measurement campaigns to quantify emissions from marginal wells. Aerial measurement campaigns (such as NASA AVIRIS or Methane Air) could also be a useful tool in quantifying emissions from marginal wells.

We can manage what we measure. Once marginal wells are better understood, both voluntary initiatives and regulatory action can be used to encourage closure of the worst-polluting wells. Carbon markets can also be put to the test. While still nascent, there is a growing industry of companies (such as ClimateWells) offering carbon credits for early closure of low-producing oil and gas wells.

More research is needed, but marginal wells could also potentially be converted into long-term profitable assets through repurposing these sites as carbon storage repositories, geothermal generation assets, or produced wastewater storage facilities. Future federal funding will be critical for research and development to repurpose marginal wells. Such funding through grants could also provide technical assistance and help finance marginal well closure and restoration. A mixture of public and private resources will likely be needed to address the large and growing population of marginal wells that span much of the United States.