Bringing Solar Within Reach: A Guide for Tax-Exempt Entities to Deliver Affordable Energy to Low-Income Households

How the Renewables Investment for Social Equity (RISE) program expands solar access in underserved communities

Important Note: Potential Policy Changes

The RISE model described in this guide relies upon provisions in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, including tax credits and the direct pay mechanism. However, as of the publication of this report, these tax credits and the eligibility for third-party-owned solar systems are being actively debated in the US Congress, which could significantly impact the viability of these approaches. This guide summarizes potential program modifications to respond to a range of future policy scenarios (see The Future of RISE section for more information)

Introduction

Low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities have historically been excluded from the cost savings and other benefits that solar energy can offer. Although LMI residents make up 46% of the US population, only 26% of residential solar installations had reached these communities as of 2023. This disparity stems from a range of persistent barriers, including high up-front costs, limited access to affordable and trustworthy financing, and the fact that many LMI households lack sufficient tax liability to fully utilize federal clean energy tax credits. Additionally, community mistrust, fueled by aggressive or misleading marketing practices, further complicates efforts to expand solar access in these underserved areas.

A new mechanism — direct pay, or elective pay — has unlocked a major opportunity: tax-exempt entities can now receive direct cash payments from the IRS equal to certain tax credits. This approach forms the basis of the Renewables Investment for Social Equity (RISE) model, in which tax-exempt organizations serve as solar owners, install systems for LMI households at low or no upfront cost, and use direct pay to claim the Clean Electricity Investment Tax Credit (ITC). For a foundational overview of how the RISE model works, including key design elements, implementation challenges, and strategies to address them, see RMI’s Insight Brief, Scaling Low-Income Solar with the Inflation Reduction Act.

RISE model

From January 2024 to June 2025, RMI convened a RISE cohort of eleven communities exploring and implementing this model. Each team included one or multiple stakeholders, such as state or local green banks, community development financial institutions (CDFIs), local governments, community-based organizations (CBOs), and private-sector partners, to design and pilot LMI solar programs tailored to their communities.

RISE cohort members

This guide builds on the experiences and insights of the RISE cohort. It is designed for tax-exempt entities seeking to adopt the RISE model or leverage direct pay to bring the benefits of solar to LMI communities. Drawing from lessons learned, practical challenges, and successful strategies tested by cohort members, this step-by-step resource provides a roadmap for turning opportunity into action. While there is uncertainty around the long-term availability of federal clean energy incentives, the final section of this guide offers strategic recommendations to help RISE programs adapt and thrive in a changing policy environment.

Determine Solar Project Type and Build a Team

The first step in planning a RISE program is to determine the solar project type and establish a team responsible for each phase of implementation. This foundation will set the program up for success.

It is important to decide at the beginning of your program what type of solar project(s) you will create. The type of project will affect ownership structure, outreach, and financing. The types of programs can include:

- Single-family rooftop solar: A tax-exempt solar system owner signs individual leases or power purchase agreements with each household, bundles multiple projects together, selects an installer, and installs solar panels on their rooftops. The household would receive the electricity produced by the solar panels, lowering their electricity demand from the utility, and reducing their electricity bill. Example: Capital Good Fund’s Georgia BRIGHT program.

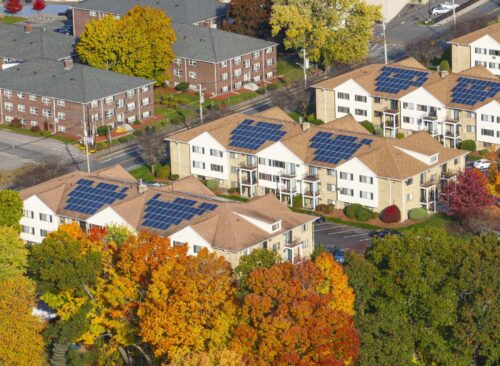

- Multifamily solar: In a multifamily housing complex owned by a single property management entity, solar panels can be installed on-site and owned by a third-party tax-exempt organization that enters into a solar lease or power purchase agreement directly with the property owner. The property owner then passes the energy cost savings on to tenants, who see an automatic reduction in their monthly electricity bills. Example: 500 kW solar at Corban Commons, an affordable housing senior living facility in Columbus, OH.

- Community solar: A tax-exempt solar owner installs solar systems within the utility service territory of the target residents. Individual LMI residents sign separate subscription agreements with the solar owner, either receiving a share of the electricity output and a reduction on their utility bills or getting a separate credit payment. Example: 808 kW Henderson-Hopkins community solar in Baltimore, MD.

Assembling a well-structured and committed team early on is critical to program success. In particular, the program manager role is essential to define before the program begins. The table below outlines key roles, responsibilities, and guidance on when to assign each.

| Role | Responsibilities | Likely Responsible Stakeholder | When to Assign Responsibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Program Manager |

|

|

Before a program starts |

| Solar Project Owner (must be a tax-exempt entity to leverage direct pay) |

|

|

During the program design phase |

| Financier |

|

|

During the program design phase |

| Community Outreach Lead |

|

|

During the program design phase |

| Solar System Host (not required for single-family rooftop solar program) |

|

|

During the program design phase |

| Solar Installer Selection Committee |

|

|

During the program implementation phase |

| Solar Installer |

|

|

During the program implementation phase |

Identify Project Ownership Structure

Determining project ownership early provides clarity and direction for the rest of program planning. There are different types of entities that can own the solar system; however, they must be tax-exempt to be eligible for direct pay. Project ownership will shape how cash will flow, who is liable, and how residents will receive the benefits of the project.

The solar system owner will be responsible for filing the necessary forms to claim tax credits. While any tax-exempt entity can be the solar system owner, the following types of actors are the most likely candidates:

Green banks

Green banks are mission-driven institutions that use innovative financing to accelerate the transition to clean energy. There are green banks in most states, but not all, and some are willing to finance projects across the nation. Depending on its capacity and structure, a green bank could be well-suited to own solar infrastructure and pass on savings to low-income residents.

Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) LLC

Although leasing is not a eligible activity, these tax-exempt entities can still create a separate LLC to own the solar systems. The CDFI will still apply for and receive direct pay incentives while the LLC would own the system, receive capital to pay for the system, collect payments from residents or subscribers, and make debt payments to capital providers.

Case Study: Launched in September 2023, Georgia BRIGHT is the first solar lease program in Georgia specifically focused on LMI households. It was developed by Capital Good Fund (Good Fund), a Rhode Island-based nonprofit CDFI. To implement the program, Good Fund established Georgia BRIGHT Solar LLC as a subsidiary to manage the entire process — from customer acquisition and developer engagement to lease payment collection. As the owner of the solar systems, Good Fund applies for the ITC through direct pay and leverages an escrow account managed by an agent to disburse ITC payments to the LLC. This structure enables Good Fund to leverage direct pay benefits while providing a scalable solar leasing solution for LMI communities.

Georgia BRIGHT’s ownership and debt structure

Third-Party Nonprofit

If a green bank or another entity is driving the project, but they do not have the capacity, financial and legal infrastructure, or a large enough balance sheet to own a solar system, they can find a third-party 501(c)3 as an owner instead. This approach not only brings in a partner with the necessary operational and financial strength but can also help insulate the initiating entity from potential legal and financial liabilities associated with ownership. They may choose to create a new special purpose entity or partner with an experienced external entity with sufficient bandwidth.

Case Study 1: Columbus Region Green Fund (CRGF), a green bank in Columbus, OH, is driving a single-family rooftop solar program and a multifamily solar program for low-income residents. CRGF partnered with the Columbus Partnership, a nonprofit organization representing the Columbus business community. The Columbus Partnership ran the procurement process to find developers for the project and set up an additional 501(c)3, Clean Energy Ventures, to own the solar systems. Doing so separated liability from the green bank and still allowed for the owner to claim direct pay.

Case Study 2: The Nevada Clean Energy Fund (NCEF) issued a Request for Proposals (RFP) to identify an organization to support implementation of the third-party ownership solar program under NCEF’s Solar for All award, for both residential and commercial systems. NCEF will work with a third-party tax-exempt entity to own and operate the single-family rooftop solar systems and pass on the 20% savings required under Solar for All.

Case Study 3: The State of Colorado issued an RFP to find a tax-exempt organization that will serve as a third-party owner for clean energy systems sought out by nonprofits. The Governor’s Office realized that nonprofits around the state would like to take advantage of direct pay, but they often do not have the capacity or resources to navigate the process. As a result, the state decided to pilot a model in which they will pay a third-party, non-profit entity that will install and own solar systems on interested nonprofits’ properties. By contracting with a single entity to own solar systems across the state, Colorado hopes to facilitate the uptake of more solar by providing a streamlined, easy way for local non-profits to benefit from direct pay with significantly lower transaction costs.

Local Governments, Municipal Utilities, and Electric Co-ops

City and county governments, municipal utilities, and electric cooperatives with ambitious clean energy goals and a strong focus on energy affordability may be well-positioned for ownership. In particular, these types of organizations may be able to leverage their existing billing infrastructure and knowledge of the local grid to streamline billing and optimize system benefits.

The solar owner and program manager may be interested in eventually transferring system ownership to residents. This may be desirable if the solar owner doesn’t have the capacity to continue to own a system long-term, or if enabling participant ownership as a means to support long-term wealth-building is an important local priority. If this is a priority for your program, consider the following legal requirements for direct pay:

- The owner who claims direct pay must retain ownership of the system for at least 5 years to avoid the IRS clawing back some of the ITC. We recommend retaining ownership for at least 6 years to be safe.

- The future transfer cannot be obligatory due to IRS rules around direct pay, which are intended to prevent gaming the system.

- The transfer recipient must pay for the system at fair market value.

- If the solar system is sold, destroyed, or removed from use, a prorated amount of the tax credit must be paid back to the IRS.

A community owner transfer will look different depending on the program type:

| Project Type | Transfer Options |

|---|---|

| Single-family rooftop solar | The solar owner can provide an option to transfer ownership to residents, but it should not be mandatory. |

| Multifamily solar | In a multifamily housing complex, such as an affordable housing building, owned by a company or organization, the solar system owner and building owner should decide if ownership transfer is desired. Tenants in the building likely would not be given the option to own the solar system. |

| Community solar | The solar owner can provide an option to transfer ownership to subscribers. |

When designing the program structure, a key consideration is determining who will collect payments from residents, including any monthly solar lease, PPA, or subscription fees. The program manager may collect payments directly, coordinate with the utility, assign this role to the solar owner, or engage a third party. Establishing a new payment collection platform can be costly, so it may be more practical to involve a party that already has the necessary infrastructure in place.

Although the solar owner is typically responsible for maintaining the solar panels, this responsibility is often contracted out or incorporated into the agreement with the installer.

Case Studies:Capital Good Fund’s Georgia BRIGHT program provides rooftop solar to residents through a lease model, allowing households to benefit from reduced utility bills. Residents make a monthly solar lease payment to Georgia BRIGHT. Although they still receive a utility bill, the combined cost of the solar lease and the utility bill is lower than their original bill, thanks to the electricity generated by their on-site solar system. The lease starts at a lower monthly rate to provide immediate savings and includes a 2.69% annual escalator.

Climate Access Fund, a Maryland-based nonprofit green bank, owns the solar panels in a community solar program, Solar4US, but they do not have the infrastructure to accept payments from subscribers and do ongoing subscriber enrollment in the event of churn. Instead, a subscription coordinator, Neighborhood Sun, is responsible for ensuring the project is fully enrolled, collecting payments, and sending those payments to CAF.

Plan Capital Stacks and Conduct a Financial Assessment

In order for RISE programs to achieve long-term savings for customers, it is critical to carefully plan project capital stacks and secure low-cost financing to manage solar projects’ significant upfront costs. Multiple funding sources described in this section can be layered to form a capital stack to finance a project.

The ITC under Section 48, the predecessor to the Clean Electricity Investment Credit (Section 48E), has a long history supporting US commercial and residential solar projects. In its current form, if the prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements are met, the ITC has a 30% base tax credit with up to an additional 40% bonus tax credit, which can significantly offset solar project costs.

ITC Breakdown

Tip: Plan for bridge financing to pay for the project upfront. Program owners can only file for tax credits after the project is placed in service.

Debt financing can include, but is not limited to, green bonds, municipal bonds, and low-interest loans.

- Green bonds and municipal bonds may enable tax-exempt entities to issue debt specifically for RISE programs.

- Government agencies, green banks, CDFIs, private investors, and other foundations with program-related investments may offer low-interest loan programs that can help finance RISE programs with favorable repayment terms.

- A short-term bridge loan is commonly employed to address initial funding needs prior to the receipt of direct pay for tax credits.

When planning for lending, it’s important to know that the amount of the ITC may be reduced by up to 15% if tax-exempt bonds are used to finance.

SRECs are certificates created for each megawatt-hour of electricity generated from solar energy systems that can be purchased and retired to support renewable energy usage claims. In particular, utilities, businesses, and institutions with the goal of achieving 100% clean energy typically need to procure RECs in an open market, and SRECs trade at a premium to non-solar RECs in some markets. As such, selling SRECs into the market can provide RISE program owners with an important additional revenue stream; however, if this approach is used customers will not be able to legally claim to be using renewable energy.

Tip: Learn how the RECs market works in your state here. Different states and jurisdictions have their own rules for regulating the RECs market.

Crowdfunding allows individual investors to contribute directly to RISE programs. These contributions can be donations or equity or debt investments. In addition to providing access to capital, crowdfunding campaigns can also serve as a marketing tool to increase exposure and awareness. You might consider leveraging existing crowdfunding platforms, such as Raise Green.

Tip: Plan for the administrative capacity and associated costs. While crowdfunding offers the possibility of raising critical and flexible funds from a variety of sources, including your local communities, it can potentially add more burdens to project owners than other financing approaches. It is labor-intensive to complete the required documentation and forms for crowdfunding. The more individual investors, the more time and effort you need to invest in communication and administration.

Revolving funds describe a special mechanism of directing the revenue or savings from completed projects to fund new projects. For example, RE-volv’s Solar Seed Fund collects a portion of revenues from each solar project to support the next one, allowing them to help more community-serving nonprofits go solar.

Tip: Revolving funds always involve long-term commitment and planning efforts. Get leadership’s buy-in and align the goal with your partners early.

Grants can come from a variety of entities, including but not limited to federal, state, and local governments, foundations, and corporations. Some grants may involve a competitive selection process. Check out this detailed Funding Guidance to learn how to prepare for grant applications.

Tip: Stack grants with other resources. In most cases, a single grant cannot cover all project costs. It might be necessary to stack multiple grants and stack grants with other types of funding.

RISE programs have the potential to maximize utility savings for low-income residents by covering a significant proportion of the upfront costs through tax credits.

There are many approaches to conducting cost comparisons, including the RMI Green Upgrade Calculator (GUC) for residential solar installations. We recommend you follow the demo and tailor the upfront incentives and financing options to your programs. Below is an example showing the impact of various ITC and grant percentages on residential bill savings.

(Example of single-family house residents in Buffalo, NY)

| Percentage of Total Upfront Costs Covered by ITC and Grants | 30% | 40% | 60% |

| Average 25-Year Electricity Cost Savings per Household | $46,000 | $51,000 | $61,000 |

Note: Residential savings are also impacted by solar system performance, local electricity prices, total project costs, net-metering policies, etc. To get the most accurate results, confirm all system specifications and other assumptions to ensure that they match your situation.

Solar4Us at Henderson-Hopkins: capital stack

Source: Climate Access Fund

Issue RFI/RFP to Select Solar Installers

Selecting one or more solar installers is one of the core responsibilities of the RISE team. It’s essential to vet installers carefully to ensure they meet the campaign’s needs and support its goals. Additionally, using a competitive selection process — such as an RFI or RFP — can help increase the chances of securing a group discount.

In an RFI or RFP, it is important to explicitly describe the program’s goals and needs. The full installer selection committee (see “Develop the Core Team ” section) should co-develop the RFI/RFP to ensure all priorities are accurately reflected. By clearly outlining specific requirements and evaluation criteria, such as a preference for including a local workforce development program, you will attract qualified developers who can best satisfy your community’s priorities and interests.

For support in developing your own solicitation, see Capital Good Fund’s RFP for a solar engineering, procurement, and construction contractor (EPC) for a single-family rooftop solar program in Georgia.

If you’ve created clear proposal evaluation criteria in your request and designated an evaluation committee, the process to select developers should be straightforward. Follow these steps to evaluate proposals:

- Aggregate RFP responses into an easily comparable format

- Meet with the Solar Installer Selection Committee and evaluate proposals using a clear scoring process

- (Optional) Invite top-rated installers for a brief phone call or interview to ask more questions and discuss their process

- Select one or more installers and negotiate the contracts

You can learn more about how to select installers here.

Plan Community Engagement and Recruit Participants

Community engagement is key to building trust, promoting inclusion, and recruiting participants for a RISE program. To do this effectively, the core team should have a strong understanding of the target audience, including their values, motivations, communication styles, and any concerns they might have. It’s especially important to align outreach messages with both program goals and the specific needs of the community, particularly when working with LMI groups who have often been left out of these conversations. Thoughtful, inclusive engagement fosters stronger participation and creates a lasting impact.

When reaching out to community members, especially LMI residents, it’s important to consider both individual messaging (e.g., saving money) and community-focused messaging (e.g., improving air quality and supporting local jobs). It can be helpful to use an online calculator, such as RMI’s Green Upgrade Calculator, for assistance in calculating individual economic and environmental benefits.

Here are some primary themes to consider emphasizing in your messaging:

Types of messaging

Identifying the key message requires input from multiple stakeholders, including not only local governments and financial institutions but also local CBOs. To support stronger CBO engagement in the RISE cohort, RMI provided special honorariums to three organizations — Groundwork Ohio River Valley, One Montgomery Green, and People’s Housing+ — to help foster partnerships with their local RISE program managers and provide critical feedback on key messages.

Because the RISE ownership structure can be complex, the program manager should be ready to anticipate and address common questions from residents about how the program works. Below is a list of frequently asked questions gathered by RISE cohort members.

(★ only applies to single-family rooftop solar programs. ▲ only applies to multifamily solar programs)

General

- Is this program legitimate?

- What is the program timeline?

- What are the short-term and long-term benefits of participation?

Eligibility

- Are there any income or credit score requirements for participation?

- Is this program available for renters?

- Can I install solar on multiple properties through this program? ★

- Will I need to replace my roof before installing solar panels? ★

Economic Impact

- Do I need to pay anything up-front or along the way to participate?

- How much is the monthly payment? Does it increase over time?

- What happens if I can’t make a payment?

- How much can I expect to save on my monthly energy bill?

- Will I receive multiple energy bills, or will everything be consolidated?

- How long will the savings last?

- How can the savings be shared with tenants? ▲

- Am I still responsible for payments if the system does not produce as expected?

- What will happen if I move away?

- How will this program affect my eligibility for the Residential Clean Energy Credit? ★

- How will this program impact my home insurance, property values, and property taxes? ★

Operation and Maintenance

- Who is responsible for system repairs and routine maintenance?

- Will the system provide backup power during an outage?

- Who is responsible for insuring the solar system? ★

In addition to clear messaging, assembling a team of trusted community representatives is essential for effective outreach and building public trust. Here are some of the most effective messengers:

1. Local CBOs: These organizations, which have established relationships within the neighborhood, are valuable partners. They facilitate engagement with residents — particularly those who may be hesitant — by leveraging trusted, existing communication channels.

Case Study 1: To keep communities at the center of their work, the Nevada Clean Energy Fund (NCEF) set up five Solar for All Community Councils: Multifamily Affordable Housing, Persistent Poverty Communities, Labor, Local Government and Schools, and a Tribal Advisory Board. The Persistent Poverty Communities Council, made up of local nonprofits, churches, and grassroots groups, has been holding regular discussions and playing a key role in informing NCEF’s outreach strategies. These trusted community voices helped inform how NCEF communicates with the public. As NCEF moves into the implementation phase, several nonprofit partners will also serve as Solar for All Champions, delivering in-person solar education sessions in LMI neighborhoods and assisting households with applications to NCEF’s programs. Grounded in local relationships and experience, these partners help cultivate awareness and build trust in the program within the communities NCEF aims to serve.

Case Study 2: Utah Clean Energy learned that traditional outreach methods for solar, such as cold calls and door-knocking, didn’t work in underserved communities. Therefore, as part of their successful Solar for All grant proposal with Utah’s Office of Energy Development, they introduced “community energy liaisons”: trusted, local individuals embedded within CBOs across the state. These liaisons serve as on-the-ground messengers, helping residents navigate solar options in a relatable, approachable way. By dedicating almost 10% of their program budget to outreach, Solar for All of Utah is investing in relationships that make clean energy accessible and community driven.

2. Partner nonprofits: Organizations such as schools, community land trusts, affordable housing groups, and home repair nonprofits with strong local connections can also play an important role in outreach, helping to convey information in a manner that is both authentic and familiar to residents.

Case Study: In Duluth, MN, SUN and One Roof co-created a community land trust model to help LMI residents go solar. In this model, One Roof owns the land, making the homes more affordable for income-qualified buyers. Because all homeowners in the program are already income qualified, identifying eligible participants for rooftop solar is streamlined. SUN and One Roof work together to install solar on these homes, building on trusted relationships and an existing affordable housing structure.

3. Solar ambassadors: People who have already installed solar, either through the RISE pilot program or on their own, can share their stories and make the process feel more approachable. It is especially powerful when these ambassadors are members of the local community.

4. City officials: When mayors or city council members show support, whether by attending events, sending mailers, or posting on social media, it adds credibility and helps the campaign reach more people. Backing from these trusted local leaders can significantly enhance a program’s visibility and help build further momentum.

When choosing outreach tactics, think about which communication channels are most likely to reach your audience effectively. For example, do they tend to engage more with traditional media or social media? Are they more likely to attend in-person workshops or prefer virtual events like webinars? Many solar campaigns have found the following outreach methods to be effective: sending mailers, using email marketing, leveraging local media, utilizing social media, being present at community events and spaces, hosting in-person solar education sessions, and planning solar tours.

See RMI’s Solarize Guide for step-by-step online guidance on how to expand residential access to solar energy by launching a “Solarize” campaign. The guide provides more information on how these outreach strategies work.

Case Study: On the Hawaiian island of Molokai, Shake Energy Collaborative — a RISE cohort member — partnered with Hoʻāhu Energy Cooperative Molokai, a tax-exempt solar owner formed in 2020, to engage the local community in designing two community solar projects: a 250 kW and a 2.2 MW solar-plus-storage installation. Despite challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, Shake and Hoʻāhu succeeded in involving a broad cross-section of residents by hosting bi-monthly Zoom meetings on Saturday mornings for over a year. These meetings shaped everything from battery sizing to contractor selection. Shake’s standout approach was “co-design,” using physical tools, such as stickers, cardstock solar canopies, and custom activity grids, to spark meaningful conversation and creative input on project details such as subscriber benefits. While online surveys fell flat, hands-on, visual engagement proved highly effective. The two projects are expected to serve up to 1,500 of the island’s 2,500 households and have already received 20% Low-Income Communities Bonus Credits. This case illustrates the power of authentic, participatory engagement, especially when outreach is tailored to how people like to learn, interact, and influence decisions in their community.

Once there is sufficient community interest and support, the program moves into the contracting phase. When working with participants to finalize official solar leases or subscription agreements, you can utilize the following agreement templates to streamline your process:

- Capital Good Fund’s solar lease template for the Georgia BRIGHT program

- New York Community Solar Subscription Agreement Sample

Construct Projects

Even after all the contracts are signed, program managers will still need to actively monitor the construction of projects to ensure smooth delivery to customers. While single-family rooftop solar and multifamily solar projects can be physically installed in a few weeks, the entire process from contract signature to system operation might take several months. A community solar project may take longer to acquire the permit, coordinate with the utility for interconnection, and build the project. Solar developers are expected to work closely with the program manager, solar project owner, and system host throughout the process.

Although the majority of the steps to install a project should be completed by the developer, program managers should monitor the developer’s progress overall and partner with developers on systemic bottlenecks as they arise. As a reference, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) outlined the typical rooftop solar adoption process to obtain permission to operate (PTO) with installers, authorities having jurisdiction (AHJ), and utilities.

Roof top solar project construction timeline

Case Studies:

Columbus Region Green Fund (CRGF) is supporting the solar deployment in Corban Commons, where an affordable housing senior living facility will host a 480 kW rooftop solar system, and the energy savings will be passed down to the residents of the facility in the form of rent reduction. The project planning began in March 2024, and it took four months to prepare the site for construction. The installation itself took one month. The project is expected to come online in May 2025.

Climate Access Fund (CAF) received the preliminary interconnection approval for the Henderson-Hopkins community solar project from the Baltimore Gas and Electric Company in February 2022. The project was restructured later to take advantage of the new direct pay mechanism. As the low-income bonus credit program requires the facility to be placed in service after receiving the credit allocation, CAF carefully planned its construction timeline to comply with the terms. The construction started in January 2024 and lasted for eleven months. The project got the credit allocation in late September 2024 and passed the final inspection in March 2025. The project began operation in April 2025.

Claim Tax Credits via Direct Pay

Direct pay allows tax-exempt entities to access the ITC to recover costs of making clean energy investments after the project is placed in service. RISE program owners should prepare for tax filing once the project has launched.

- Determine tax filing year: Tax-exempt owners should prepare to claim tax credits the next tax year after the project starts operation. For example, if using a calendar tax year, projects going online in 2024 need to be filed for tax credits in 2025.

- Complete the pre-filing registration in advance: IRS recommends tax-exempt owners pre-register at least 120 days before they intend to file their tax returns that include the direct pay or transfer election.

- Properly value the tax credit basis: Tax-exempt owners are responsible for correctly calculating the tax basis when using direct pay. The total grant, donation, forgivable loan funding, plus direct payment cannot exceed the total project costs.

- Keep all the records: Tax-exempt owners should provide documentation that is sufficient to prove compliance with IRS requirements, such as the prevailing wage and apprenticeship (PWA) rules. Keep documentation for seven years in case you are subjected to an audit.

Case Study: RE-volv is a nonprofit solar developer that helps other nonprofits in underinvested communities go solar in the U.S. In June 2023, RE-volv installed a solar system at a no-cost charter school located in Plumas County, northern California. Nearly half of the students come from low-income families. With a 40% tax credit, this 55.76 kW solar system is expected to generate more than 1.9 million kWh and save nearly $730,000 over the installation life. After filing for tax credits in July 2024, RE-volv got its direct payment from the IRS in August 2024.

RE-volv’s direct pay timeline

Manage the Program

To keep the RISE program running smoothly, it helps to have regular check-ins with core team members, community partners, financial institutions, and solar installers. Maintaining regular communication in this way makes it easier to coordinate the necessary tasks, avoid misunderstandings, and keep the program moving forward.

The RISE program manager should assign a team to handle ongoing support for participants. This individual will serve as the main point of contact for addressing resident questions, resolving complaints, and working with installers to quickly manage any construction issues or maintenance requests that may come up.

Starting at least five years after the project’s online date, program managers can begin discussions with participants about the potential to transfer solar ownership to residents. For more information, see the section titled “Plan Community Ownership Transfer Options” under “Identify Project Ownership Structure.”

The RISE program manager should be responsible for continually tracking the program’s impact in relation to its goals. RISE cohort members summarized the following metrics to track during the community engagement and program operation phase:

| Category | Metrics |

|---|---|

| Community Engagement |

|

| Community Participation |

|

| Economic Impact |

|

| Environmental Impact |

|

The Future of RISE

RISE programs have the potential to deliver significant benefits to residents, especially in underinvested communities. Their success will depend on deep collaboration across multiple stakeholders — green banks, CDFIs, local governments, community-based organizations, private investors, electric utilities, and others.

Although the current set of RISE programs were designed to take advantage of existing incentives and structures, many of these policies may be revised or cancelled in the future. As the policy landscape continues to evolve, entities pursuing RISE programs could consider the following adjustments to their program designs to adapt to various potential policy shifts:

| Scenario | Solutions |

|---|---|

| If the ITC bonus credits are reduced or canceled | Increase the proportion of debt in capital stack planning and explore other available opportunities to bridge the gap. |

| If the available federal grants are reduced or canceled | Diversify funding sources by tapping into local and state grants, crowdfunding, and support from foundations and philanthropies. |

| If the ITC base credit is reduced over time | Accelerate project timelines, starting construction and placing the system in service as soon as possible. |

| If direct pay is revoked | Shift to having a private entity own the assets, as in a traditional Solarize model, while still retaining a focus on meeting LMI community needs. |

| If third-party solar leases are not eligible to claim tax credits anymore | Consider having a nonprofit or commercial entity own the solar assets and share a portion of the savings with community members through direct payments. |

If the federal clean energy tax credits shift, there are still paths forward. RISE programs, when grounded in strong community collaboration, can weather these changes and remain feasible and impactful.

Special Thanks

Blair Freeman Group, Capital Good Fund, Climate Access Fund, Center for Rural Affairs, Cincinnati Development Fund, City of Cincinnati, City of New Orleans, Columbus Partnership, Columbus Region Green Fund, DC Green Bank, Finance New Orleans, Greentech Renewables, Groundwork Ohio River Valley, Hawaii Green Infrastructure Authority, IMPACT Solar, Lawyers for Good Government, Leon Lowenstein Foundation, Montgomery County Green Bank, Nebraska Investment Finance Authority, Nevada Clean Energy Fund, One Montgomery Green, People's Housing+, RE-volv, Shake Energy Collaborative, Solar United Neighbors, SustainEnergyFinance, The Port of Greater Cincinnati Development Authority, Utah Clean Energy, Waimea Nui Community Development Corporation.